N&M 2013 | post-exhibition essay

If we could bottle light

Meg Walker

Surprises make a child of us: here is another. A moon rising, edge so sharp you can feel it in your back teeth. … Unexpectedness moves us along. And the moon – so perfectly charted – never fails to surprise us. I wonder why. The moon makes a traveler hunger for something bitter in the world, what is it? I will vanish; others will come here, what is that? An old question.

– Anne Carson1

Imagine the things we could share if we could capture light. Not just the imprints and effects of light, but light itself: the physical, moving thing that touches the surfaces of phenomenon around us and lets us understand at least something with our eyes before we touch with our skin. If we could bottle light, we could experience time differently too, saying: here’s a sliver of sun from a morning that knew mammoths; here’s a bright flare from the first night your city used electricity; here is the light from the day you turned four.

Recreating a condition of light that existed elsewhere is an intriguing way to bring us into a contemplation past events. The two installations in this year’s edition of The Natural and The Manufactured connected with long swathes of time by wrapping visitors in light conditions that offered contemplation of past phenomena as much as past human events. Slowing down to observe them was a bit like slowing down to watch a sunset or a blaze of sundogs in the sky, opening the possibility of altering our sense of time’s speed, too.

The Homecoming (Sarah Fuller, AB) and Welcome Stranger (Paul Griffin, NB) both changed dramatically when their lighting changed. Their transformations were unapologetically beautiful, nuanced and enticing, as well as expertly crafted and carefully thought through.

On a leafy August evening, small groups of people walked through Sarah Fuller’s installation The Homecoming in the woods that were once part of Bear Creek, a former townsite a few kilometres southwest of Dawson. We were waiting for the “magic hour” – the period of warm, golden sunlight that photographers wait for at the end (or start) of each day. The duration of pinkish-orange light lasts longer than an hour this far north, which Fuller observed during her visit to Dawson City in summer 2012. She created The Homecoming for that specific time of day.

Fuller works in both large-format photography and digital video and is actively engaged with photographic techniques across the centuries. With The Homecoming, she created five large-scale photographs of houses that were originally homes in Bear Creek, and now exist as homes in Dawson City. Bear Creek was the local administrative headquarters for companies that ran massive dredges through the gold-bearing creeks in the Bonanza Creek area from 1905 to 1966.2 The five homes Fuller used were moved to Dawson during the late 1960s and early 1970s. During the installation, Fuller placed signs in front of these buildings in their current locations, describing briefly the family ownership of each and when they were moved.

The Homecoming drawsinspiration from earlier history too, including Louis Daguerre’s diorama techniques for theatre. Before the success of the daguerreotype, the image-fixing invention that preceded photography, Daguerre had partnered with engineer Charles Bouton in the early nineteenth century to invent painted backdrops that were translucent in some areas and opaque in others. The images would “move” as theatre workers moved shutters or screens to alter the light on the paintings, in a fully darkened, rotating theatre. From the start, according to Daguerre’s notes after he opened the Diorama in 1822, the spectator expected the illusion “to represent the effects of nature.”3

Two key ideas from the diorama inventions appear in The Homecoming, though of course Fuller may have drawn from multiple sources. First, she adapted the idea of activating a large-scale image through changes in light. Using large-format photography, Fuller took contemporary images of the Bear Creek houses and inserted them into photos of the forest that has taken over parts of the former town site. She printed the hybrid images on strips of linen, sewed them together and painted the backs blue, which left the houses opaque except for the window areas.

Next, Fuller hung the images between birches and spruce that now thrive in the spots the houses once stood.4 High-powered work lights were set up behind each one. When the right amount of paleness lit the sky, the artificial lights would glow through the imaginary panes of glass and balance with the natural light. For several minutes each night, the houses looked as if someone was home, waiting for visitors and friends to knock at the door.

The second idea borrowed from Daguerre’s diorama is Fuller’s decision to move the audience through the images, instead of moving the images directly. The installation is not an attempt at theatre, but instead leads to a jump in time. It presents a moment in Bear Creek history that emerges because of the quality of light at a particular time of day. We experienced textures and hues that would have been there when Bear Creek was bustling, that began long before Bear Creek was even imagined, and that continue now.

In the trajectory of Canadian art history, there has long been a push against the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century notions of landscape as a wilderness that supplies a backbone to Canadian identity. Art historian Peter White comments that, since the 1960s, artists, historians and others “have been actively engaged in the process of re-examining landscape in the process of its traditionally instrumental, universal and strongly sentimental role in the construction of Canadian identity.” Once the dream of a modernist Canada slipped into one of post-industrialism and late capitalism, he says, “traditional history was displaced or superseded by the less codified and personal imperatives of memory in understanding or relating to the past.”5

The Homecoming joins this flow by offering a “wilderness moment” that is also a domestic one. The installation brings specific household memories into the semi-wild forest space and, because the only way to see it is by walking through the woods, it also points to the forest’s lifespan, a timeframe longer than the lifecycle of a wooden house. Landscape and personal/national identity are thus explored together, instead of demanding a hierarchy.

Paul Griffin, in turn, embraces the impact of romanticist notions of landscape on human activity – not on the landscape itself – by looking to the gold exploration history in Victoria, Australia, for the source of Welcome Stranger. He named his sculpture after a gold nugget discovered on Friday, February 05, 1869 near Moliagul, a small town north of Melbourne.

An immigrant named John Deason was prospecting for gold when his pickaxe struck something hard at the bottom of a stringy bark tree, the story goes. As he tried to pry the mysterious chunk out of the ground, the pickaxe broke. Deason called for his co-miner Richard Oates to help and they pulled up an irregular mass of gold intermixed with black quartz.

They named the nugget “Welcome Stranger,” likely because the largest nugget previously found in Australia before had been named “Welcome” – in retrospect, a colonialist’s dream of an “empty” land relieved at the chance to be worked and brought into the relentless streams of “progress.” Deason and Oates spent the next two days heating and cooling the nugget, to break the quartz away. On Tuesday, the miners took the nugget to nearby Dunolly, the closest bank, but the bank’s scales couldn’t handle the weight. Solution: they found a blacksmith’s shop and cut it into smaller pieces.

In less than a week, most of the “Welcome Stranger” nugget was melted into ingots; the miners kept a few chunks for themselves and their friends, but the soon-to-be-mythologized shape itself was gone. By February 21, the ingots were on a steamship to London. “Welcome Stranger” ended up containing 2316 troy ounces of gold (just over 71 kg), making it the largest alluvial gold nugget ever found in the world, to this day.

Surprisingly, both Deason and Oates carried on prospecting, continuing their working lives. This is where Griffin’s sculpture picks up the narrative and takes it down a different stream. Deason and Oates’ sweat-driven willingness to pickaxe their way through dusty ground had paid off dramatically. Arguably, they could have looked at their new wealth and been satisfied, especially since they had been mining the area for some time and knew it wasn’t rife with giant nuggets. But they were in it for the dream, the thirst for another moment of awe, another experience of wonder. Or so we might imagine, looking back.

The Welcome Stranger sculpture starts with the lustre of the dream, turning the nugget’s name into a metaphor for a person’s experience of feeling they are “called” by the wilderness, the journey, the gold itself. Griffin, a former logger and carpenter, combined precision and fluidity in a compelling way. He used dozens of metres of fishing line to hang 5,500 four-inch metal deck screws in the outline of an irregular, oblong, somewhat oval shape hovering over a “shadow” of stones laid on the floor.

Griffin spent hours hanging the fishing lines in perfectly spaced rows, which gave the light a “corridor” effect when the eye caught the straight line for a moment among the otherwise imprecise shape. The low angles of the gallery lights added to the illusion of a strobe caught in slow motion. It was a seductive, delightful experience to get lost in the Welcome Stranger’s sheen and weightlessness.

The “nugget” spanned 24 by 12 by 9 feet at its longest, widest and highest dimensions. Each time people walked by, bringing their own subtle breezes, a few screws would move and lightly strike each other. The sounds were delicate, enticing. During the dozen or so visits I made, it seemed that the moment anyone heard them, the bell-like chimes intensified an already-present desire to run fingers along the fishing lines as if running them over a musical instrument or a chainlink fence.

No direct images are left of the “Welcome Stranger” nugget today: no models, photographs or direct drawings were made before the melting began. Various replicas of how the nugget likely appeared are based on a drawing made from memory after the fact, according to the report to the Mines Minister on February 12, 1869.6 Thus, even if Griffin had wanted to make a sculpture based on the nugget’s factual size, dimensions and visual features, it would be de facto approximate and, by extension, curling towards the realm of desire, of elusive dream. So it is fitting that Griffin created an experience

of yearning.

Griffin’s sculpture elegantly separated thousands of screws from their typical relationship with machine time and suspended them, for a few weeks, in the qualities of time relating to searching, questing, roaming. In his own search for the Welcome Stranger sculpture’s shape, Griffin looked to Chinese scholar’s rocks – appreciated as tools for meditation and for cultivating beauty – as an example of stones valued outside of commerce. Following this route, Welcome Stranger can be read as the shimmering outline, the ghost shroud, the spiritual and porous border of a not-quite-solidified shape of knowledge still to come, that will never quite be held in hand. Yearning is the hunger that creates energy for moving us through the practical. Our internal wilderness demands a dream that draws us forward.

Because the nuances of Welcome Stranger and The Homecoming depended on seeing the artworks shift as the light changed, they eluded definitive documentation. Uncertainty is embedded not only in archiving any sculpture or installation, but also in “capturing” any natural phenomenon. What would the authoritative image be – one with the screws motionless or as they sway? The larger question then becomes: why do we want to encapsulate a time-based experience in a flat, two-dimensional image, or even a four-dimensional video archive? What is the source of the desire to freeze a moment in time?

Each year’s opening weekend for The Natural and The Manufactured also includes a lecture by a writer, exploring our interactions with the ecosystems that surround us and that we assemble. Robert Bringhurst, a poet and linguist well known for his work in translating Haida and Navaho literatures in particular, was the guest this year. His image-rich, associative presentation included challenging us to think about machine-encoded time and whether the machines we’ve made are driving us, or whether we are still making decisions about how we want machines to fit into our lives. If we immerse ourselves only in machine-time, he proposed, we end up losing the ability to experience, much less appreciate, cultural ways of being that exists on forest time, or sun time, or ocean time, or animal time.

Bringhurst’s poetic speech was not a direct reflection on The Homecoming and Welcome Stranger, but all three events were immersed in understanding time as a changeable phenomenon instead of a stringently measured one. The outward-folding, sensual experiences that came from passing an interval with The Homecoming and Welcome Stranger can be understood as physical metaphors of relationships with time that are harmonious, not confrontational. The art works were optimistic and leave behind, at least for a while, the commerce-driven use of time as chronology.

The upswell of creativity that carries art from individual minds to publicly shared spaces is a surge that can’t be kept measured and segmented. This is why art – including art about landscape, art about light – doesn’t remain tied for long to any governmental or state agenda. More personally, when art touches more than just the artist and the few people who know him or her, it also eludes being tethered to individual chronologies of memory. It draws us into experiences larger than that of a single personality.

The urge to freeze an experience in a “perfect moment in time” comes, in part, from our awareness that we’ll want to recreate the experience later, either for ourselves or for others. We know it’s impossible to call any image a record of “now” – already gone by the time the shutter closes or the fishing line dangles – yet we find resonant beauty in our relationship with that elusiveness. Maybe this is for the best. “If we look at time as the physicists do,” writes poet Christopher Dewdney, “it makes more sense to think of time as an ocean. We and everything else in the universe float, or bob, in this fluid medium. The present, past and future are merely drifting currents.”7 If we could grasp all the moments of time in one handful of perfect, shiny nuggets, what yearning would be here to keep us swimming forward?

– Meg Walker, Dawson City

1. Carson, Anne. “The Anthropology of Water” in Plainwater: Essays and Poetry. Vintage Canada, 2000.

2. Lewis Green’s book The Gold Hustlers (Alaska Northwest Publishing Company, 1977) gives a detailed look at the competitive business wranglings that drove Joe Boyle and A.N.C. Treadgold to fight for financing, water, and of course gold, as they ran the dredges. The first dredge ran under the Canadian Klondyke Mining Company; the last under the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corp.

3. For the purposes of appreciating The Homecoming, the storyline in focus is the social one. The town was a going concern, to use an old saying. It had a bunkhouse, individual houses, a gold room and machine shop. In fact, because large-scale machinery was required to maintain and repair the gigantic dredges, Bear Creek had the biggest machine shop in western Canada for a time, with equipment that included a 10-ton overhead crane, five lathes of differing sizes, and a 900-ton hydraulic wheel press. The dredges ran 24 hours a day for about 250 days each year, stopping only when heavy ice formed in the ponds.

4. Daguerre, Louis-Jacques-Mandé. An historical and descriptive account of the various processes of the daguerréotype and the diorama. London: McLean & Nutt, 1839, quoted on http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Daguerre’s_Diorama

5. In the summer of 2012, Fuller located the houses in Dawson City, visited the current owners, and photographed the buildings as well as locations in Bear Creek that became the homes’ new, artificial, backdrops. During the winter, she printed them, transferred them to squares of linen and then sewed them into images about 80% real-life scale. Come summer 2013, she carefully hung the homes among the spruce and birch at Bear Creek and lit them from behind.

6. White, Peter. “Out of the Woods”, in Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity and Contemporary Art. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007.

7. http://members.westnet.com.au/likelyprospects/welcome_stranger_nugget.html

Dewdney, Christopher. Soul of the World: Unlocking the Secrets of Time. HarperCollins, 2008.

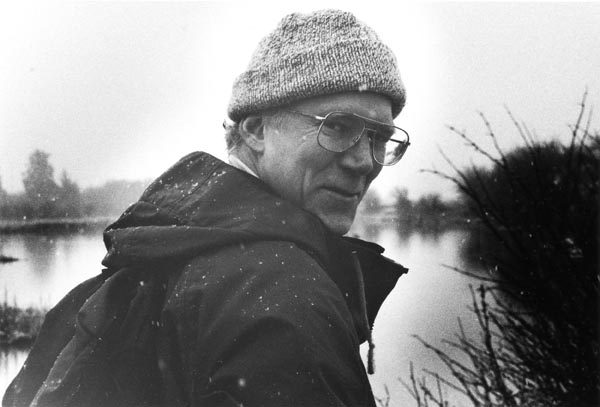

Meg Walker alternates writing with art-making, hiking between the topographies of sight and word.. Her wanderings across Canada landed her in Dawson City four winters ago and, thanks to the incredible invention called the internet, she continues to write from here for magazines and small-press publications. Recent work includes “Crocus Bluff – open arms” as part of the group show Traversing Yukon Landscapes at the Yukon Art Centre, Whitehorse.