Post-exhibition essay for The Natural & The Manufactured 2015

COURTNEY HOLMES | TRACES OF INDUSTRY

The small hamlet of Dawson City in central Yukon is best known as the home of Canada’s first great gold rush — an event which brought with it massive geographical changes upon which the modern community is built. The legacy of the decades-long search for gold in the hills and valleys of the Klondike remains imprinted on the land and psyche of the small wilderness town.

The Klondike Institute of Art and Culture’s artist in residence program plays host to The Natural & The Manufactured — an annual arts project that invites artists to compose site specific works in response to the economic and cultural values of the region.

Colin Lyons and Kevin Murphy participated in the 2015 edition of The N & M. Both artists recently spoke of their experience with Courtney Holmes, current Executive Director of the Yukon Art Society. These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

COLIN LYONS | TIME MACHINE FOR ABANDONED FUTURES

Courtney Holmes: There has been some discussion lately at a local level about whether the dredge tailings are worth preserving. Some have suggested removing them all; others want them to stay. A third suggestion is to remove all but one, preserving it as a full-fledged artifact. Which course should Dawson City pursue?

Colin Lyons: As an outsider, I don’t think it’s my place to decide. My preservationist instinct would compel me to leave things as they are, as a haunting reminder to the unchecked speculation and environmental devastation that was brought on by the gold rush. Seen from the Midnight Dome, the tailings offer an unmistakable glimpse into the lasting effects of industrial development and extraction-based economies.

Given the environmental impact of these industrial projects and the harm they create, how does nostalgia fit in?

In industrial ruins, we are confronted with past notions of progress and utopia, which have since proven to be failures but leave visible traces of their unfulfilled promises. I think post-industrial ruins serve a vital purpose, as a kind of counter-narrative.

We now live in a world where the struggle to keep up often leaves us frozen in the present, unable to fully imagine a future. The reaction, we see time and again, is nostalgia for the past.

What are examples of nostalgic industrial utopia that exist in Dawson City or elsewhere?

Part of my hesitation about restoring the tailing piles is exactly this issue. Without them, Dawson risks becoming a place which rests on the nostalgic tropes of the Klondike gold rush era, while glossing over the human and environmental costs of this history. This was part of my fascination with the tailing piles — that they can be read as a lasting authentic ruin of the Klondike gold rush.

How does your upbringing in Petrolia inform your interest in Dawson City?

Growing up in Petrolia, I was constantly surrounded by evidence of industrial obsolescence: Victorian mansions, a massive playhouse, and slowly-bobbing pumpjacks. All pointed to a place which had fallen on tough times after a period of great promise. Petrolia’s very reason for existence was founded on oil. As the country’s first oil boomtown, the men flocking there never thought about whether this was a renewable or non-renewable resource. Of course, as is the inevitable fate of any boomtown, the oil slowed to a trickle by 1908, and my sleepy hometown has spent over a hundred years fading into irrelevance.

Petrolia and Dawson City followed similar trajectories until relatively recently, when Dawson took on renewed significance as a centre for the arts and tourism. In many ways, Dawson City is an ideal place to consider the ideas that came out of my Petrolia experience: it’s a place where industry has irreparably shaped the landscape; where the residents have had to do some soul-searching about its very reason for continued existence; and where there are ongoing questions of what to make of the material remnants of its golden era.

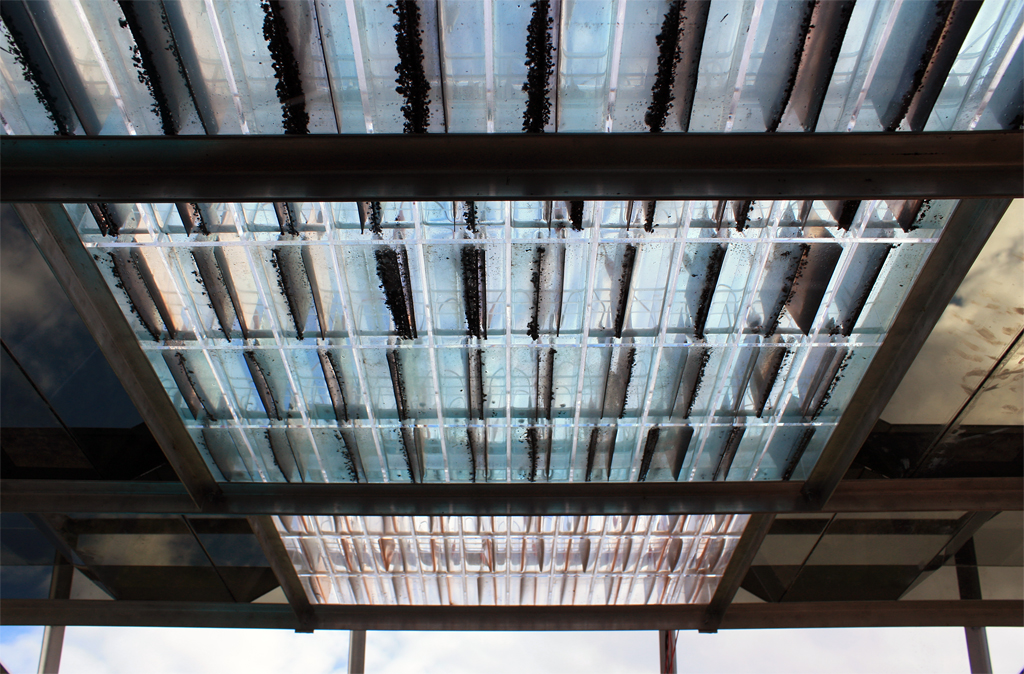

Time Machine For Abandoned Futures. Detail: Gold rush artifact in etching acid undergoing electrolytic cleaning process. Installed on the Midnight Dome, August 2015. (Photo credit: Colin Lyons)

Does gentrification relate to these landscapes?

Gentrification is a term specifically used when discussing the relationship between a location and class dynamics (the displacement of a lower class for a higher one), which I feel is not exactly what is happening here. However, there is a kind of glossing over that can come along with the historicizing of a place.

With the reconstruction and tourism of Dredge No. 4 for instance, the tailing piles become background or setting for understanding the grandeur of the post gold-rush projects. In that context, I found myself thinking “wow, that’s brilliant,” instead of “that’s horrifying.”

Do you have a specific thought or statement that Dawson City residents should take away from your art?

No, nothing that precise. The reality is, those who have spent decades immersed in this environment are going to see my work much differently than I do. Also, since this installation was perched on the side of the Midnight Dome, the audience was equal parts tourist and resident.

There seemed to be a kind of compartmentalizing of the landscape, where visitors hoped to witness either the vast northern wilderness, or a mecca for mining and industrial history. I hoped to reorient the gaze from the Dome to acknowledge this complicated legacy, and force a collision between these two notions of the landscape.

With my Time Machine, I attempted to highlight that binary approach to the landscape by subverting the utopian architectural form of the Earthship, creating instead an inefficient and wasteful system. I hope to bring to light the ways in which so many of our modern industrial projects are using antiquated and wasteful technology, yet attempt to project an air of progressivism.

Finally, I hope this project helps further the discussion about what to do with the legacy and ruins of the gold rush. I think the tailing piles can be read as a kind of accidental monument.

KEVIN MURPHY | ONE SQUARE INCH MORE OR LESS

Courtney Holmes: Can you explain your research process for this installation?

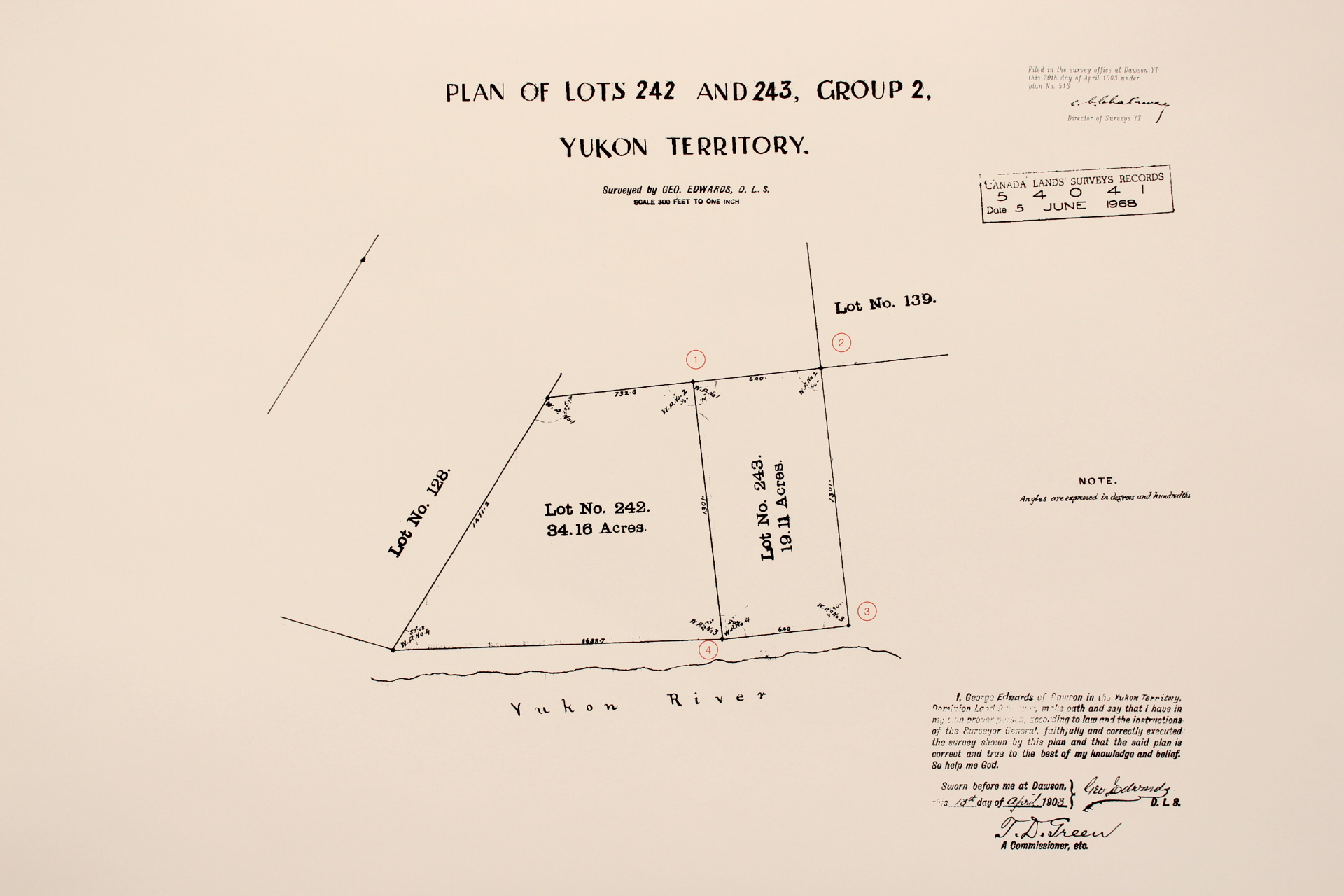

Kevin Murphy: The research for this project was extensive. It took place online, in books, through visits to the Dawson Archive and local historic sites, and through correspondence with Yukon Land Titles, Natural Resources Canada, and Quaker Oats, among others. Much of it relied on technology, from easy communication with various parties, to sourcing the deeds on EBay, and locating the sites through GPS.

The most difficult step was determining the individual one-inch locations. Each deed is stamped with a unique alphanumeric code. Ostensibly these are locatable through a site plan, but the precise reference pattern has long been lost. Quaker doesn’t have the records anymore, and doesn’t want to talk about the promotion at all. David McDonald, who directed the film Cereal Thriller, has done a mountain of research on this, and was very generous with suggestions. In the end, I pieced it together through reference to books and articles; David’s resources; and certain mathematical parameters, including the lot dimensions and the range of deeds that were printed.

Once the site plan formula was reconstructed, it had to be overlaid onto larger land survey plans to determine each set of GPS coordinates. Whitehorse-based surveyor Glen Lamerton generously helped with these calculations and then lent me his GPS unit to locate the sites.

Was this Quaker Oats promotion a form of colonialism?

Well, it certainly mimicked and utilized colonial systems insofar as it involved the division and widespread distribution of Crown land. But more than this, as a fantasy representation of land, I see Quaker’s project as a fascinating cultural example of “landscape.” Cultural critic W.J.T. Mitchell refers to landscape as a form of soft power, a permeable social construction that is “something like the ‘dreamwork’ of imperialism.1″ For Mitchell and others, Western landscape traditions appear natural, but hinge on imperial and colonial fantasies embedded in territorial consumption and expansion. In North America, these fantasies have especially been tied to the romanticized West and North. One line by Quaker’s own legal team provides a particularly perceptive analysis: “the real value of the deeds was based on the romantic appeal of being a property owner in the Great Yukon Territory rather than on any intrinsic value of a one-inch square of property.2” I think what’s wonderful about the Big Inch promotion is this visible connection between the romantic and the economic. When the deed holders linked the representation of land to its physical occupation and ownership, the promotion collapsed under its own weight, beautifully exposing the underlying tensions.

The promotion was essentially an invasion of the imagination. It valued the land not for what it was but for its imagined romantic nature in the minds of southerners who had never actually been there. Do you see parallels between this habit of mind and modern relationships between North and South?

Sure, and I think Dawson has built a lot of infrastructure around these processes of romantic projection and their crystallization in tourism economies.

For me, as a southern/Vancouver artist trying to propose a site-specific project for a place that I had never been, this idea of imaginative projection also felt like an appropriate reflection or refraction of my own position. Entering the artist residency period with only a distance-based and thus surface understanding of Dawson implicated me in a way that felt honest, and created, I think, a kind of parallel to the imaginative responses of these children, decades earlier.

One Square Inch More Or Less (detail), 1958 survey of land referred to in Quaker Oats’

Klondike Big Inch Land Co. promotion. ODD Gallery exhibition, 2015

Because so much of the legal precedent surrounding land and property is based on possession, occupation and use, do you feel like you settled or have some ownership of these tiny parcels of land?

No, I felt very conscious that I was working in a space that didn’t belong to me, and possessing the deeds heightened that awareness. But the ownership of land, and particularly its abstraction and representation as title, is certainly one idea I’m investigating.

Something to note about the deeds is that in Western Canada, we are on the Torrens system, which means land ownership is transferred through registration of title instead of using deeds. So a “land deed” is not a legally recognized document in Yukon at all. The Klondike Big Inch Land Co. was created primarily for the U.S. cereal market, so Quaker used broadly U.S. terminology. It’s just another fiction among many.

The land itself was repossessed by the Canadian government in the 1960s for non-payment of taxes, and it’s been bought and sold since then. So although I purchased them, the deeds have been divorced from this land for more than fifty years, and really, I would argue, since their creation. In some ways, this project is about re-establishing a link between the deeds and the land they signify, and also about the impossibility of doing so.

What do you think of the fact that this land is now a golf course? Is there any narrative worth exploring there?

The land isn’t actually the golf course, but is directly adjacent to it. That turned out to be an often-repeated misconception that sprang up around later discussions of the promotion.

The land with the deeds is privately owned and most of the sites I visited were in the forest, some areas thinned, and some quite dense with new growth. One site was in a tire rut on a dirt lane, another was in a horse corral, and a third was beside the rotting and overgrown remains of a burned out building….

Were consumers tricked? How much did a notion of injustice play in this installation?

I’m less interested in injustice to consumers than I am in these implicit and historical injustices that come with the whole framework of deed as representation.

I’m not convinced that Quaker ever expected anyone to want to physically claim the land. For me, the most surprising thing about the whole enterprise was that its developers made the journey in person to see the property.

I suppose that consumers may have been tricked insofar as the land was not legally attainable, but I actually agree with Quaker’s lawyers that the land was not what they were really selling. I think where Quaker misstepped was in allowing the fantasy to unravel, which in turn revealed that the fantasy was merely a fantasy.

__________________________________

1W.J.T. Mitchell, “Imperial Landscape,” Landscape and Power, 2nd ed. (Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 2002), 10.

2 Arthur F. Marquette, Brands, Trademarks and Good Will: The Story of the Quaker Oats Company (New York: McGraw Hill, 1967), 121.

Courtney Holmes is the Executive Director and Curator with the Yukon Arts Society in Whitehorse, Yukon. A graduate of the Yukon School of Visual Arts in Dawson City, Holmes has previously worked for non-profits and youth organizations in Yellowknife, NWT and Iqaliut, NU. Holmes is also a past member of the ODD Gallery and KIAC Artist-in-Residence Committee.