The 2011 Natural & Manufactured post-exhibition essay

BELONGING IN DAWSON

by Megan Graham

Every year, the ODD Gallery invites artists to participate in The Natural & The Manufactured project, a six week-long residency in Dawson City, Yukon. During this residency, artists explore significant issues such as landscape, consumer culture, and meaning in order to “stimulate and engage people in a re-examination of the various cultural and economic values imposed on the environment, while exploring alternative political, social, economic and aesthetic agendas and strategies towards a re-interpretation of the regional landscape and social infrastructure.” 1 In addition to the assigned theme and approach, the artists must present their work in the ODD Gallery or in a public art installation at the end of the residency.

The Natural & The Manufactured residency challenges the artists to create new site-specific works based on their stay in Dawson, which requires a certain amount of effort in engaging with the community rather than using the residency to work on ongoing projects. Ideally, all artists who participate in the year-round KIAC Artist in Residence program get involved with the town, but they are usually able to do so without the pressure of immediately displaying recently created work that reflects their engagement and understanding of the community. The format of the residency raises several questions: is meaningful engagement and understanding achievable in the course of six weeks? How can artists successfully complete this assignment?

For their time in Dawson, the artists buy expensive groceries, walk on the dyke, drink Pilsner at the Pit until last call, exceed bandwidth limits—essentially, they live the Dawson lifestyle, and they fit in easily due to the diversity of the population. For the purposes of this residency in particular, art historian Lucy Lippard’s notion of “sense of place” might serve as an answer to the question of belonging or engagement during the residency. In her work The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, she defines sense of place as “a way for nonbelongers to belong, momentarily.” 2 The goal for the artists becomes a way of belonging that is momentarily meaningful, a way that goes beyond drinking a shot containing a shriveled toe.

For the 2011 residency, Bill Burns (Toronto), Deborah Stratman (Chicago), and Steve Badgett (Chicago) utilized distinct strategies to meet the thematic requirements of the project, as well as exhibiting a nuanced sense of place that explored the psychic geography of Dawson in surprising ways. Rather than falling into the pitfalls of the “Artist as Ethnographer” 3 or by attempting some “authentic” representation of the town by regurgitating a clichéd visual identity, the artists incorporated facets of their Toronto and Chicago practices and selves into their work inspired by Dawson, resulting in a higher collaboration and engagement that genuinely belonged.

Stratman and Badgett’s public art installation Augural Pair consisted of two six-foot tall pine viewing stations. The first scope was installed on Second Avenue between Queen and Princess Streets. There was no explanatory plaque or sign, and the only decoration on the smooth blond wood was an electron shell diagram for gold, element 79 in the Periodic Table of Elements. The scope looked to a second-level window at the CIBC Bank, where a red digital display listed the current price of gold as provided by a live internet feed. Through the viewfinder, the commodity of gold is reified as we see the arcane value of the precious metal discretely quantified. Though the concept of gold’s value has been made real through its quantification, it becomes clear that we still cannot reach this gold which we desire; the scope emphasizes our distance.

Stratman and Badgett’s public art installation Augural Pair consisted of two six-foot tall pine viewing stations. The first scope was installed on Second Avenue between Queen and Princess Streets. There was no explanatory plaque or sign, and the only decoration on the smooth blond wood was an electron shell diagram for gold, element 79 in the Periodic Table of Elements. The scope looked to a second-level window at the CIBC Bank, where a red digital display listed the current price of gold as provided by a live internet feed. Through the viewfinder, the commodity of gold is reified as we see the arcane value of the precious metal discretely quantified. Though the concept of gold’s value has been made real through its quantification, it becomes clear that we still cannot reach this gold which we desire; the scope emphasizes our distance.

Similarly, the second scope in Augural Pair (also six-foot tall, but lacking any inscription) was placed on the bank of the Yukon River, looking up and across to a mirrored disk installed on land belonging to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation. The reflective disk was surrounded by realistic life-sized sculptures of ravens that responded to the mirror and invited interactions with live ravens. Again, through the use of the viewfinder and the division of the river, the viewer’s distance from the object is emphasized. Likewise, desire was heightened as anything in peripheral vision turned to black through the viewfinder. Depending on the weather, the form of desire changed. On a pleasant day with no clouds, the mirror reflected the blue sky in a bright, obvious way, creating the desire for something to extract. On a gray, overcast day, the disk resembled a hole in the landscape, exposing a desire for something that had already been extracted, or the need to be whole.

Similarly, the second scope in Augural Pair (also six-foot tall, but lacking any inscription) was placed on the bank of the Yukon River, looking up and across to a mirrored disk installed on land belonging to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation. The reflective disk was surrounded by realistic life-sized sculptures of ravens that responded to the mirror and invited interactions with live ravens. Again, through the use of the viewfinder and the division of the river, the viewer’s distance from the object is emphasized. Likewise, desire was heightened as anything in peripheral vision turned to black through the viewfinder. Depending on the weather, the form of desire changed. On a pleasant day with no clouds, the mirror reflected the blue sky in a bright, obvious way, creating the desire for something to extract. On a gray, overcast day, the disk resembled a hole in the landscape, exposing a desire for something that had already been extracted, or the need to be whole.

Viewers familiar with Dawson and the Yukon could identify the site-specific elements of Augural Pair. For example, the subject of gold was a timely inclusion in the project. In the summer of 2011, the historic Gold Rush town was buzzing with the idea of a second gold rush. GroundTruth Exploration, a local mineral exploration company, boasted an increased summer staff of over 70 soil samplers or “dirtbaggers,” ostensibly correlating with the appearance of new expediting and helicopter companies. 4 The Discovery Channel’s Gold Rush: Alaska filmed its second season of the mining reality TV show in the area. Even The New York Times had an extensive article about the Yukon’s mushroom forager-turned-millionaire Shawn Ryan of Ryanwood Exploration. 5

Viewers familiar with Dawson and the Yukon could identify the site-specific elements of Augural Pair. For example, the subject of gold was a timely inclusion in the project. In the summer of 2011, the historic Gold Rush town was buzzing with the idea of a second gold rush. GroundTruth Exploration, a local mineral exploration company, boasted an increased summer staff of over 70 soil samplers or “dirtbaggers,” ostensibly correlating with the appearance of new expediting and helicopter companies. 4 The Discovery Channel’s Gold Rush: Alaska filmed its second season of the mining reality TV show in the area. Even The New York Times had an extensive article about the Yukon’s mushroom forager-turned-millionaire Shawn Ryan of Ryanwood Exploration. 5

Likewise, the incorporation of ravens into Stratman and Badgett’s project was a logical choice. The Common Raven is ubiquitous in the Yukon Territory, and is thus frequently employed in representations of Dawson. The highly intelligent birds hold a sacred place in regional mythology as beloved tricksters and world creators. Specifically, Augural Pair draws on a traditional story of how the raven stole the sun and released it into the sky. 6 Stratman and Badgett’s carved birds fit seamlessly into this story, as they held court as cautious guardians of the covetous shiny orb. Furthermore, the title of the project, Augural Pair,references the ancient Roman augur, a religious official who observed and interpreted natural signs, especially the behavior of birds, to determine divine approval or disapproval of a proposed action.”augur”. 7 There could be no better choice for such a bird in Dawson than the raven.

Although the content of Augural Pair clearly employed Dawson iconography, the framework or narrative structure of the story that Stratman and Badgett extracted from their residency had all the distinct markings of their artistic practice. Stratman is primarily a filmmaker concerned with “how history plays out in the land.” A common theme in her films and public interventions is surveillance, whether being watched by someone or something else, as in the 2002 film In Order Not To Be Here, or a self-surveillance of emotions, as evidenced by Fear, an ongoing project in which participants call a toll-free number and describe their deepest fears. With the collective SIMPARCH, Badgett has created community-minded installations which fuse politics, humour, and utility. The collective aestheticizes sustainability in projects such as Hyrdomancy (2006), where the means of clean water acquisition is made visible. Works like Free Basin (2000), where wooden basins built for skateboarding were installed in five art gallery spaces, reflect the collective’s concern with understanding and playfully altering the purposes of a specific site. 8

Stratman and Badgett demonstrate the typical format of a residency, where artists arrive with pre-existing concerns in their practices and then find inspiration in a new, specific space. In a mutually beneficial exchange, viewers re-interpret and expand their conception of the site, and artists explore new dimensions and possibilities for their practices. This is not quite what happened with Bill Burns’ residency.

When I first heard about Burns’ intentions for his ODD Gallery show, I thought it was bound for failure—and not a sexy failure. 9 For more on failure in contemporary art practices, see Nicole Antebi, Colin Dickey, and Robby Herbst, eds., Failure!: Experiments in Aesthetic and Social Practices (Los Angeles, California: Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Press, 2007). I remember having a conversation with ODD Gallery Director Lance Blomgren several weeks before the opening of the show, where I asked, with disbelief and moderate concern, “So he’s just going to carve the names of esoteric art world figures into logs? That’s his plan?” As if that would resonate with Dawson residents, or Mean Something.

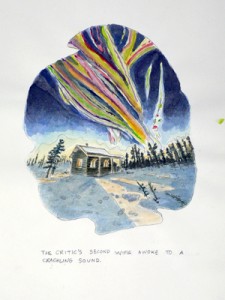

My initial response at the opening of The Veblen Good wasn’t much more nuanced. The chalkboard wall work listing “those who have helped me, those I still hope will help me, and those who wronged me” gave context and imbued humour into the massive logs with the same names inscribed into them. The Photoshopped facelifts to the S.S. Keno (now the H.U. Obrist) and a Holland America tourbus (rebranded as Martin Kippenberger Tours) provided easy laughs, as did the witty autobiographical watercolours of Burns’ outdoor expeditions with curators, collectors, and editors. This was all fine and good, but I couldn’t help feeling cheated by Burns’ show. Did he even consider the place he had been living in for the past month?

My initial response at the opening of The Veblen Good wasn’t much more nuanced. The chalkboard wall work listing “those who have helped me, those I still hope will help me, and those who wronged me” gave context and imbued humour into the massive logs with the same names inscribed into them. The Photoshopped facelifts to the S.S. Keno (now the H.U. Obrist) and a Holland America tourbus (rebranded as Martin Kippenberger Tours) provided easy laughs, as did the witty autobiographical watercolours of Burns’ outdoor expeditions with curators, collectors, and editors. This was all fine and good, but I couldn’t help feeling cheated by Burns’ show. Did he even consider the place he had been living in for the past month?

I mistakenly believed that a work that didn’t obviously reflect an engagement with Dawson couldn’t speak about Dawson on a meaningful level. This was a problem of framework. Where Stratman and Badgett used their own artistic framework to convey Dawson-specific content, it is helpful to view the autobiographical content of Burns’ work in a Dawson framework for its meaning and sense of place to be revealed. Burns’ inscription of himself into the world of Dawson is explicit (writing the names of people who have shaped his life on a blackboard, on logs, on a boat, on a bus), but the relationship of life in Dawson to Burns’ work is less deliberate.

The Veblen Good is not devoid of Dawson content. The lumber used for the engraved logs was sourced from West Dawson. Burns photographed the S.S. Keno, Holland America tourbus, and the “Building With No Name” during his residency. The name Martin Kippenberger holds significance to Dawson residents who recall the German artist’s METRO-Net project, in which he installed entrances to underground transit stations in cities worldwide, including Dawson in 1995. 10 The wildlife and outdoor travels depicted in the watercolour works would resonate with most northerners’ adventurous spirits.

But what really matters to Dawson is how Burns illustrated the social dynamics of a small town in the North in ingenious, subtle simplicity. In a town that so rigidly attempts to exhibit a coherent identity based on a four-year period in history, it becomes necessary to map new stories and heroes and values onto daily life in order to make present-day Dawson a place worth living. It requires carving a place for yourself and injecting your own brand of incoherence. It means coming to terms with the private (and public) lists of those who have helped us and those who have wronged us, because these are the people who help define us. One of the beautiful facets of Dawson is that it eludes a homogenous definition. In many ways it is a chosen community: many of its residents were not born and raised there, and its extreme remoteness requires an intentional arrival. The people who make up Dawson comprise a multitude of experiences and opinions. It’s a small town that’s anything but small-minded.

But what really matters to Dawson is how Burns illustrated the social dynamics of a small town in the North in ingenious, subtle simplicity. In a town that so rigidly attempts to exhibit a coherent identity based on a four-year period in history, it becomes necessary to map new stories and heroes and values onto daily life in order to make present-day Dawson a place worth living. It requires carving a place for yourself and injecting your own brand of incoherence. It means coming to terms with the private (and public) lists of those who have helped us and those who have wronged us, because these are the people who help define us. One of the beautiful facets of Dawson is that it eludes a homogenous definition. In many ways it is a chosen community: many of its residents were not born and raised there, and its extreme remoteness requires an intentional arrival. The people who make up Dawson comprise a multitude of experiences and opinions. It’s a small town that’s anything but small-minded.

Stratman and Badgett’s project also taps into powerful emotional territory in its exploration of desire and loss. By presenting these emotional forces in context with a shared history of gold, extraction, and traditional mythology, desire and loss become very specific to Dawson. Augural Pair poses charged sociological questions: How do you put a price on your community? Can the acquisition of our desire fill the place of things we have lost?

Just as The Veblen Good doesn’t promote a particular path or tell Dawson residents how to live, Augural Pair doesn’t provide answers or make suggestions for viewers. These are good things. There are countless examples of collaborations between artists and communities where projects end up being prescriptive, as if the momentarily belonging artist understands the needs of a community better than those who are a part of it. 11 The projects created in 2011’s The Natural & The Manufactured residency were successful because they uncovered more questions than answers in their exploration of Dawson.

In a diverse place like Dawson, there needs to be a variety of residents, residencies, projects, and frameworks for understanding. This results in a multitude of ways for artists and viewers to engage with Dawson and each other. Stratman, Badgett, and Burns actively challenged ideas of how we belong in a place and how a place belongs to us.

______________________________

BIOGRAPHY

Originally from Richmond, Virginia, MEGAN GRAHAM is an administrator and writer living in Toronto. She received BAs in Art History and English from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia and an MA in Art History from the University of Chicago, focusing on contemporary painting, video art, and activist art practices. In June 2011, she curated Every Day I’m Hustlin’, a photographic exploration of work and labour in the Dawson City area, at the Confluence Gallery. Her writing on arts and culture has appeared in Yukon-based and national publications.

Notes:

- The ODD Gallery, The Natural & The Manufactured: an ODD Gallery & KIAC Artist in Residence Project, http://naturalmanufactured.org/description.htm (November 30, 2011) ↩

- Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 1998), 33. ↩

- See Hal Foster’s admonishment of contemporary artists employing an anthropological model of visual culture in The Artist as Ethnographer in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996). ↩

- Ground Truth Exploration, Jobs, http://www.groundtruthexploration.com/#!jobs (November 30, 2011). ↩

- Gary Wolf, “Gold Mania in the Yukon,” The New York Times, May 15, 2011, Sunday Magazine, MM42. Accessed online at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/magazine/mag-15Gold-t.html (November 30, 2011). ↩

- Deborah Stratman, Artist Talk, Dawson City, Yukon, August 11, 2011. ↩

- Oxford Dictionaries Pro. April 2010. Oxford Dictionaries Pro. April 2010. Oxford University Press. 30 November 2011 <http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/augur >. ↩

- Deborah Stratman and Steve Badgett, Artist Talk, Dawson City, Yukon, August 11, 2011. For more on Stratman and Badgett’s practices and projects, see http://pythagorasfilm.com and http://www.simparch.org, respectively. ↩

- Theaster Gates introduced me to the concept of a “sexy failure,” or a surprising, meaningful, unintentional consequence, in his Spring 2009 Intervention and Public Practice course at the University of Chicago. ↩

- See Charles Stankievech, Last Train: A Wake for St. Martin Kippenberger’s METRO-Net in Dawson City, Yukon, http://www.stankievech.net/projects/metro-net/ (November 30, 2011). ↩

- Miwon Kwon provides an extensive exploration of community art projects, both successful and unsuccessful, in One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Location Identity (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004). ↩