INFO/FLOE

Finding A Pace, Sensing A Place

Josh Winkler (Mahkato/Mankato, Minnesota); and Lindsay Dobbin (Kanien’kehá:ka /Acadian/Irish based in K’jipuktuk/Halifax) in collaboration with Elder Angie Joseph-Rear, Michelle Olson and Matthew Morgan (Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in citizens) and Sharon Maureen Vittrekwa (Tetlit Gwich’in citizen).

Presented by: The Klondike Institute of Art & Culture

At The ODD Gallery, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in traditional territory (Dawson City, YT)

August 16th – September 22nd, 2018.

At Hermes Gallery, K’jiputuk (Halifax, NS)

March 2nd – 31st, 2019.

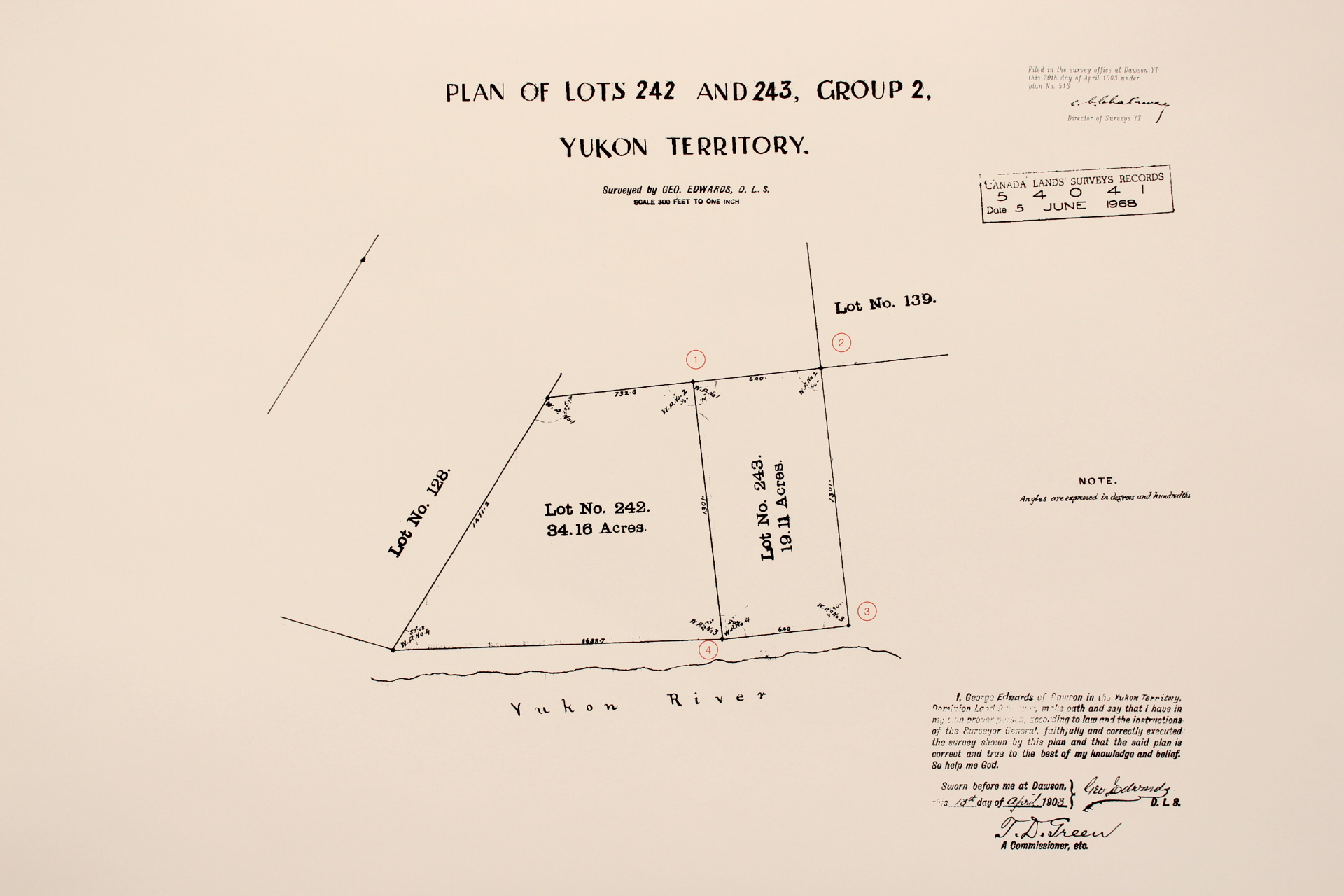

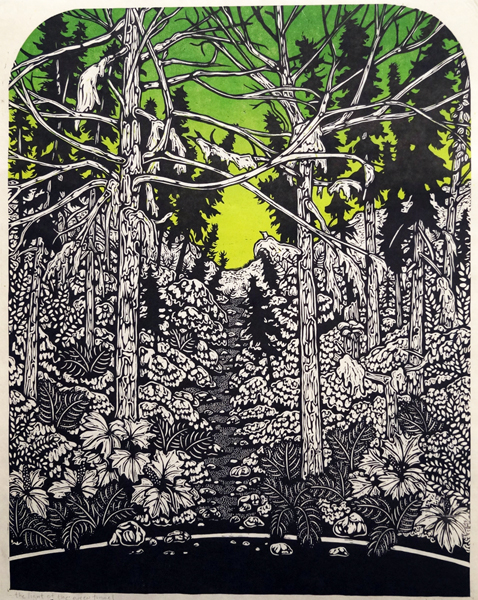

The Great Yukon River Path, colour woodcut print, 16”x20”, Josh Winkler, 2018.

“The natural world is a living archive. Landscape has memory; water carries story. I know when my body is touched by water, immersed in water, a resonance and transfer of information occurs. The water flows through landscapes and my body. It makes me of the landscape — my body, a song for the earth.”

– Lindsay Dobbin, Artist statement, Bay of Fundy, 2017

“Each time I walk a footpath, whether stamped-down snow between parking lots, a deer trail in tall grass, or an extended hike for months in the woods, I find magic and metaphor in the collective path. Started by one, then maintained through collective use, the walking path is a living history between past and present and a thriving link between species.

The pace of foot travel & river travel foster intimate connections to the land. Our species evolved to travel this way, to carry the supplies of survival, and to develop extensive knowledge of plants and animals.”

– Josh Winkler from his BLOG entry Pace, September 30th, 2018

INFO/FLOE explores multiple perspectives of interacting with the land as an active keeper of memory, archivist, and teacher, through the work of two artists whose work involves deep listening, participatory workshops, considering found materials in installation, and using print media as a documentation and communication tool. Hosted by KIAC’s annual The Natural & the Manufactured residency and exhibition, INFO/FLOE considers the information that we leave behind and accumulate through our interactions with the environment.

As curator for the 2018 edition of The Natural & the Manufactured, I invited Josh Winkler and Lindsay Dobbin to create and present new work for the program. Having met both artists personally, in the Yukon and in Nova Scotia respectively, I was drawn to their methodology and work ethic, which they foster through experiential learning. Each artist nurtures an openness to and deep interest in listening to, respecting, and protecting the land. Working with them throughout KIAC’s The Natural & the Manufactured (N&M) program, we were able to respond to the complex relationships between production and resources, colonial and corporate motives, and the increasingly relevant conversation around human impact on the environment that are so inherent in contemporary life in the Klondike region.

For The N&M, Dobbin and Winkler each developed new work emerging from an experiential approach to art making, interacting with the land and fostering collaboration. They also approached their projects with a willingness to learn from the the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people and residents of Dawson City.

Each artist’s works were created within the six weeks leading up to the N&M exhibition. The artists created with fresh eyes and ears, responding to recent experiences with a sense of immediacy and improvisation. Winkler’s work emerged from a two-week hike through the Chilkoot Trail and further shorter hikes in and around Dawson City. Dobbin collaborated remotely from their home on the Bay of Fundy in Mi’kma’ki (the ancestral and unceded territory of Lnu’k or Mi’kmaq), with three Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in citizens – Elder Angie Joseph-Rear, Michelle Olson and Matthew Morgan – and one Tetlit Gwich’in citizen – Sharon Maureen Vittrekwa.

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit: Yukon River, 2018. Photo: Matthew Morgan

The confluence of the Tr’ondëk River1 and the Yukon River 2 continues to be home to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people, who have lived alongside of, and maintained a harmonious and sustainable relationship with, the river for thousands of years. As we continue to depend on the river today, we owe tremendous thanks to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people who, while facing extreme difficulties, continue to consider the protection of water of paramount importance to the continuation of life.

Water is not only a central element in Lindsay Dobbin’s practice, but a deeply important part of their outlook and everyday experiences. Dobbin is a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) – Acadian – Irish water protector, artist, musician, curator and educator who lives and works on the Bay of Fundy in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of Lnu’k. Born in and belonging to the Kennebecasis River Valley, the traditional territory of the Wəlastəkwiyik, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy, Dobbin has lived throughout Wabanaki as well as the Yukon in Kwanlin Dün territory, and maintains a practice that includes a thorough process that acutely responds to direct experiences with ecology and places and is often equally, if not more, prominent than the final outcome of their work. For The N&M, they worked intently with a smaller group of people from a distance in Wapu’ek, which means the white waters in Mi’kmaq, on the Minas Basin, Bay of Fundy. Receive Transmit Receive Transmit uses FM radio frequencies to communicate through the air, while allowing remote participation between five individuals alongside two bodies of water — the Yukon River and the Bay of Fundy (Dobbin’s home body of water)3. Dobbin prioritized working with Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people, who continuously have been integral to maintaining respectful relationships between the ecology and people living and visiting the area.

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit: Bay of Fundy Intertidal Walk Lindsay Dobbin, 2018. Photo: Lindsay Dobbin.

Dobbin is acutely aware of the impact we make on our surroundings, whether as a mark in the sand, a splash in the water, or a sound in the air. The artist also explores how the notion of a “completed signal” overlooks the long-term impact that the communicative gesture has on the receiver. This impact, however subtle, almost always remains in some form of memory – in this case a documented natural recording. The impact may go unnoticed in our limited human sensorium, yet physically changes the shape of our surroundings, and in turn our understanding of the environment. Through effective communication,deep listening and participatory actions, Dobbin connected with each collaborator individually. They asked questions and responded to each other through conversation, syncing the pace of their surroundings by sharing descriptions and stories from each location.

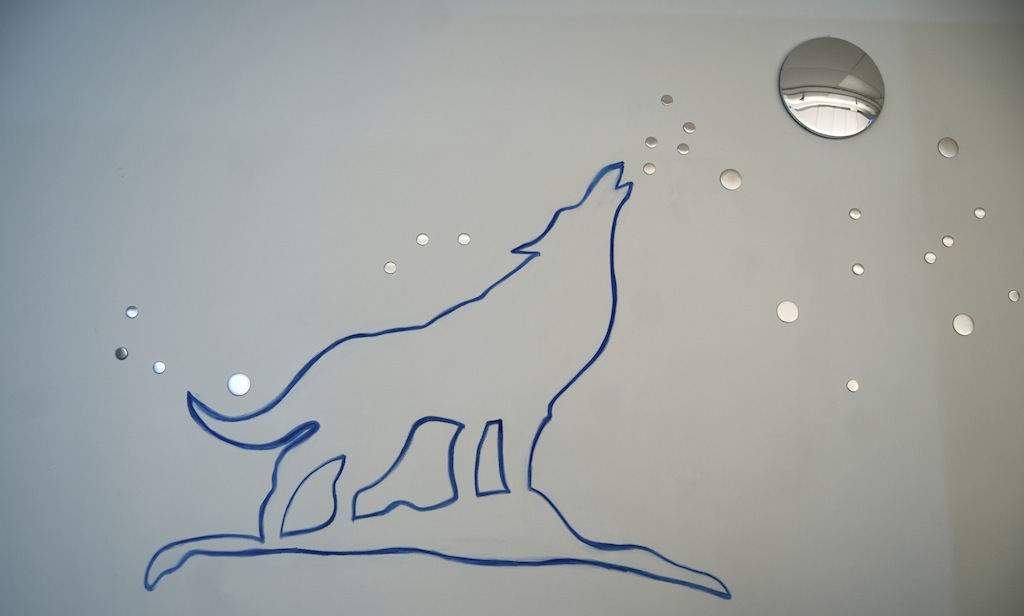

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit, Lindsay Dobbin, 2018. Photo: Michael McCormack

Radio static itself is rich with texture. As an instrument, it helps us hear frequencies we can’t hear with the human ear alone. While at first it sounds like simply noise, when listened closely to or when slowed down, one can even find rhythm in the high frequency waves. Receive Transmit Receive Transmit invited visitors to become participants, to listen to the environment and dialogue between two places over FM radio receivers while walking the land. As the participants moved throughout the town of Dawson City, or along the Yukon River, they encountered three conversations bleeding into each other through overlapping radio signals. The intimate conversations reflect perspectives shared with the land and water over extended periods of time in Dobbin’s home on the Bay of Fundy in Mi’kma’ki, and Morgan, Olson, Joseph-Rear and Vittrekwa’s experiences with the Yukon River.

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit, Lindsay Dobbin, Michelle Olson, Angie Joseph-Rear and Matthew Morgan, 2018. Photo: Tara Rudnickas

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit is both a new and an ongoing project. Informed by recent experiences, while shaping future perspectives, it invites participants to “tune-in” to each other on multiple levels simultaneously, always allowing for the time and space necessary to find each others frequencies, to move forward, together. This is reflective of much of Dobbin’s practice. For example, in 2017 they worked with Nova Scotia artist Andrew Maize to create a work titled Kite and Rodas part of the Floating Warren Pavilion and Projects (curated by Zachary Gough, in Charlottetown, PE). Dobbin and Maize connected a mic to the end of a kite, and waterproofed and connected another mic to the end of a fishing line. The resulting listening experience allowed one to hear the sound of the wind and the sound of the underwater at the same time on a single headset.

Kite and Rod Lindsay Dobbin and Andrew Maize as part of The Floating Warren project with White Rabbit Arts Society at Flotilla Atlantic, 2017. Image Zachary Gough (project curator).

You can listen to an audio recording of this collaboration on Dobbin’s Soundcloud.

With radio, we rely on the resistance of the land or water to transmit signals over long distances. Receive Transmit Receive Transmit embraces those physical facts. Depending on the listener’s location, the audio comes across with varying degrees of clarity; occasionally there may be interference from another radio station. This offers a sense of playfulness, bringing recorded conversations to life through interaction with radio, a medium more often than not associated with real-time “live” broadcasts. Through the site-responsive audio installations in and around the Yukon River, Dobbin’s work allowed listeners to move at a pace in tune with the flow of water in both geographies.

Receive Transmit Receive Transmit: Yukon River Waterline, Matthew Morgan, 2018. Photo: Matthew Morgan

In her essay Remote Sensing, critical theorist Caroline Bassett suggests, “Perhaps we should think about these interactions not in terms of the messages they carry, but in terms of the emotional punch they pack.”4 Through highlighting the emotive qualities of media distribution, Bassett draws importance around our sensorial experiences when experiencing media through television, radio, or other media distribution sources. She breaks down the term “remote sensing” as a process involving a collaboration of senses that when communicating over distance are often overlooked or misread through a hierarchy of information over feeling.

Yukon River Shoreline, Matthew Morgan, Dawson City. August 15th, 2018

Video: Matthew Morgan.

Dobbin was unable to visit Dawson City in person, and embraced distance as an opportunity to work simultaneously in multiple locations. They used remote sensing to cultivate connections with participants. This allowed for promotion of sensitivity and compassion through understanding the emotive and cultural sensitivities that are so vital to building long-term, mutually beneficial, meaningful relationships and collective resilience between people and between nations over such vast distances.

The participants of this project described their surroundings to each other, shared stories, and walked alongside their respective home bodies of water. They conversed about personal experiences, family stories, observations of wildlife, with a focus on sensorial feeling of being in each place. Through this fine-tuned communication, Dobbin, Morgan, Olsen, and Joseph-Rear were able to zero in on each other’s surroundings from a distance. Dobbin playfully requested different activities with each of the three Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in collaborators; one was to walk with them at the pace of the Fundy tides while they walked the pace of the Yukon River, another was to take pictures, to make a sound of a Raven, or sing a song.

These conversations were recorded, but only available to experience in real time as an FM radio broadcast throughout Dawson City, offering visitors an opportunity to “listen-in” on these intimate exchanges while travelling through town experiencing their own personal journey. Dobbin uses radio to bring the experience of listening to something that is not recorded, archived and kept for later, but insists on the urgency of listening in real-time through tuning in to 88.8 FM. Dobbin creates this work through a multi-tiered experience, not out of hierarchy, but out of a current need to respectfully connect first and foremost with the people of the river, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, followed then by those who experience the project as listeners.

FM transmitters were placed in three locations throughout town transmitting conversations between Dobbin, Morgan, Olson and Joseph-Rear. They could be heard on 88.8 FM throughout the entire town and along the banks of the Yukon River and were transmitted from KIAC, The Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre, and the Old Post Office. Photo: Matthew Morgan.

Minnesotan artist Josh Winkler created several new works for The N&M during back-to-back residencies: a 6-week Natural & Manufactured residency in Dawson, preceded by a two-week Chilkoot Trail Residency with the Yukon Arts Centre, Parks Canada, and the US National Parks Service.

Hiker Handout Cards – Chilkoot Trail Residency, Josh Winkler, 2018

Winkler’s work involves in-depth research and consideration of materials that are found in the area of the Klondike, recorded and reproduced as manufactured objects. Bringing these objects into the gallery setting, Winkler intersects studio and installation work, enveloping materials gathered from his walks and hikes in critical contemplation. This act problematizes, and opens a conversation with, reconsidering objects of “historic significance.”

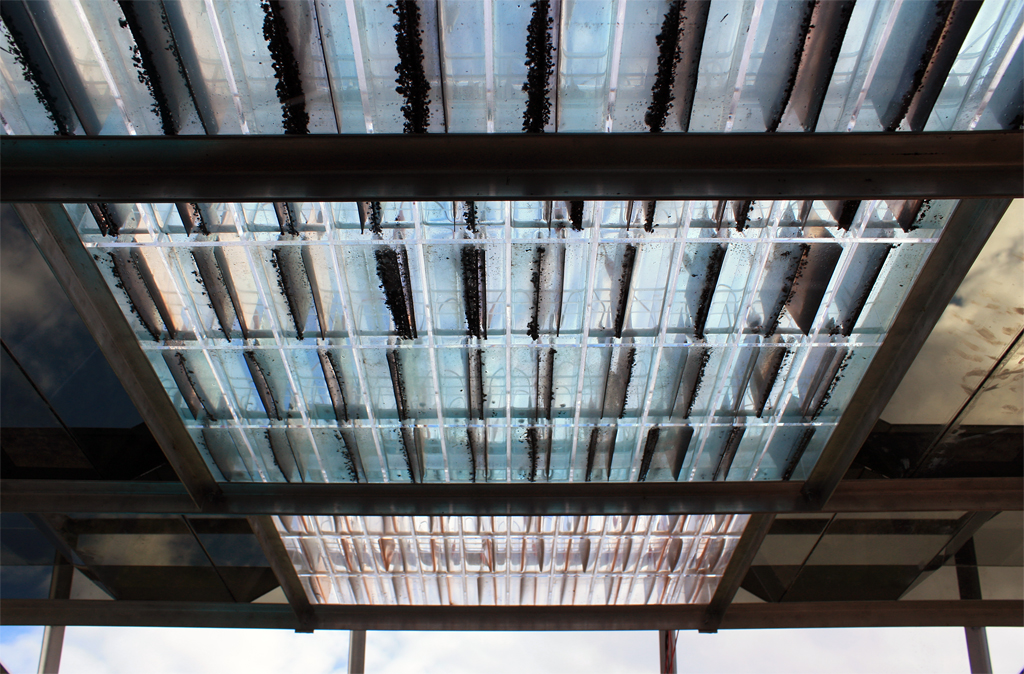

Klondike Tailings, woodcut on found wood, found objects, Josh Winkler, 2018. Photo: Janice Cliff

Klondike Tailings, woodcut on found wood, found objects, Josh Winkler, 2018. Photo: Janice Cliff

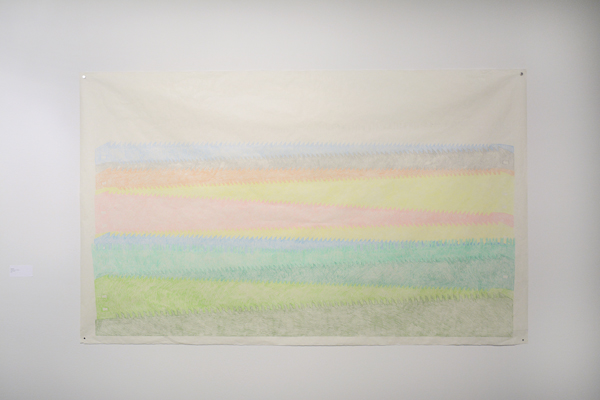

There is an incredible amount of material evidence in nearly every corner of Dawson City today. Abandoned print presses in buildings owned by Parks Canada, dredges left in tailing ponds, paddle wheelers shipwrecked on the riverside, and even a locked safe that was excavated from a construction site this past summer. The area is full of material that is preserved in climate controlled spaces by government archives or museums.5 The remains of these discarded gold rush items are considered significant enough to document, heavily research for authenticity, and sometimes marketed to tourists and reality TV shows.

Winkler is aware of these contradictions. His installations in the ODD Gallery consider our relationship with materials that at times end up in museums, but ironically are often found on the side of the road, buried underneath buildings, along hiking trails, and in garages, storage areas and dumps. The largest piece in the gallery consists of dozens of found car tires meticulously cleaned, glazed, and stacked in columns floor to ceiling in the gallery space. This piece holds together a gravity within the conversation between all of the works in the room, bringing forth a material that is immediately recognizable, while reminding us that we are active contributors to the accumulation of materials that continue to make significant environmental impact in the north and globally. The tires as columns offer a throwback to both functional and cultural aspects of western architecture, a glimpse to both a future and past apocalypse.

Column, Josh Winkler, 2018. Photo: Janice Cliff

Only very recently–starting with the 1897 Gold Rush–settlers have arrived in large numbers,6 bringing with them mining equipment, woodstoves, paddlewheelers, cars, newspapers, and many other tools and materials that have seriously altered our relationships with nature. Large scale developments have ensued, such as the construction of the White Pass Railroad, the Alaska Highway, logging roads, and recent mining and commercial fishing operations. Many of these projects have altered landscapes through large-scale erosion, contaminated water and soil, and air pollution. They have caused health issues for many rural and Indigenous communities. They have blocked off access to hunting and fishing and changed migration patterns for fish, caribou, and other animals.

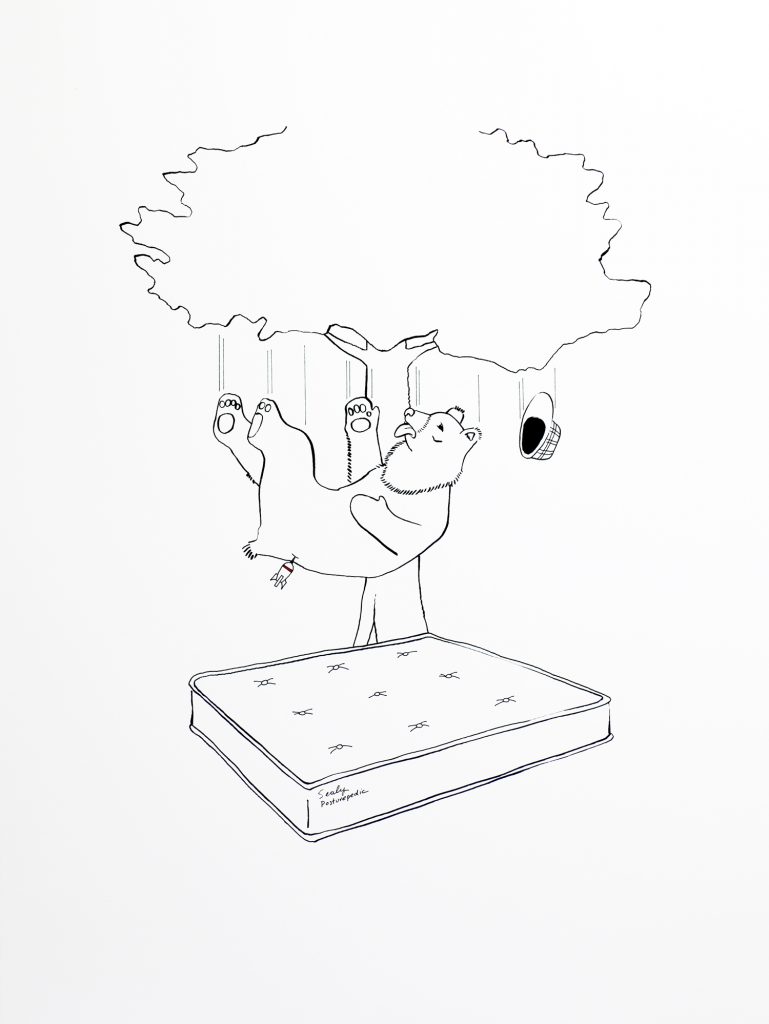

Winkler’s exhibition Climb Cut Conquer was shown in the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse in 2016. It is a body of prints and drawings that tell the story of the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees in Northern California. The work zeroes in on the destruction of the Discovery Tree through creating a graphite rubbing of the Discovery Stump as it exists today.

Josh Winkler, Discovery Stump (process shot) Josh Winkler, 2014. Photo: Josh Winkler.

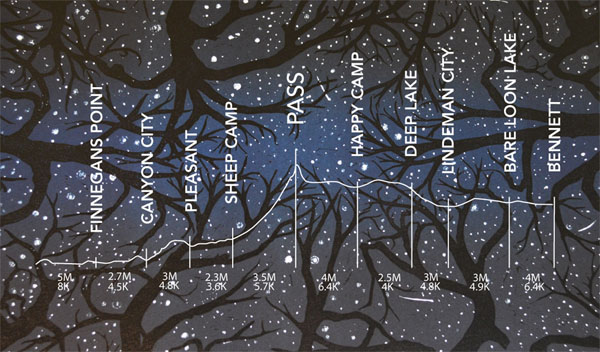

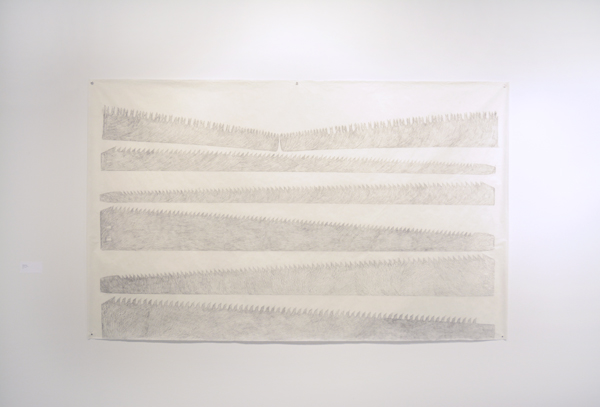

During the 6-week residency in Dawson City, Winkler created one of a kind rubbings of saw blades in his two works titled collection and horizon, illustrating how fragile and potentially impermanent memory can be. The saw blades were shown to Winkler by the Dawson City Fire Chief Jim Regimbal, who took Winkler to the Denhardt Cabin in North Dawson, one of the oldest gold rush era cabins that has not been moved. Winkler finds connections between the saw blades as images and the landscape. “I was thinking about the spruce tips defining the horizon (similar to the saw blades), the positivity of the rainbow, and the sort of ironic or playful gold rush reference,” states Winkler. With tourism placing so much emphasis on the gold rush as an iconic symbol of cultural significance in the Klondike, it is often hard to identify the many other significant attributes of the community. Winkler’s awareness and sensitivity toward this is evident in his work, acknowledging the irony around much of the gold rush era material that has been so meticulously preserved, engrained in everyday life becoming “less artifact, and more kitsch.”7

Collection (above) and Horizon (below), Josh Winkler, 2018. Photo: Janice Cliff.

A one of a kind print is unique, fragile, and relates to our place as stewards of our natural environment, and how environmental neglect can permanently affect future generations. The impact that the huge volume of material produced in and brought to the Yukon during the gold rush continues to be present, yet amidst the debris are numerous stories that are often overlooked. Much of the manufactured material that filled landfills and houses in Dawson during the gold rush still lives with us through time and is accompanied by shifting storylines told around them.

During the first half of the twentieth century, not long after the gold rush, the bond between radio and print media was still very much alive, often involving collaboration with newspapers, magazines, or sign makers. We see this throughout Dawson City, with painted signs, the Dawson Daily News building, the Old Post Office and other Parks Canada sites. Over time, our relationship with radio has changed from something that we ‘tune in’ to, calling for our undivided attention to a peripheral experience within our industrial, commercial, and domestic environments. It has turned from something we intently listen to into an accompaniment to our daily activities. As print media becomes digitized, it continues to cooperate with live broadcast media, but has now become easily manipulated and updatable.

Uncertainty around who controls the media has been continuous throughout time, and questioning authenticity of our media sources is certainly necessary to attempt to maintain power balances. Within Dobbin’s work and within the N&M Exhibition as a whole, print and radio worked as collaborators. Visitors to the exhibition could wander through town, along a footpath, or alongside the river while listening to conversations from Dobbin’s work, perhaps coming across artifacts akin to what Winkler has uncovered and brought into his installation in the ODD Gallery. Immediate surroundings, readymade artifacts, interpretive prints, and recorded audio broadcasts are woven together to make an experience that feels deeply personal and unique to your own interpretation.

Through this project, Winkler and Dobbin created work that opens new conversations between their own personal experiences with nature. They are both well aware of their relationships with material and the environment as temporary, and part of an ongoing, interconnected system that have had, and will continue to have influencers. Winkler created work reflecting on keen observations from found artifacts on previously worn footpaths of the Chilkoot trail and around Dawson City, and Dobbin created work through remote sensing and collaboration, listening to the landscape and stories of those who have lived in the area for thousands of years.

Whether walking through the town listening in on conversations about the river broadcast over radio, or experiencing work made up of collected material and interpretations of the landscapes through printed material, visitors experienced the effects of “real-time” radio, and recorded media on paper and through readymade sculptural works in the gallery.

When we consider a river, or a footpath as a means of distributing recorded information from one place to another (or from the past to present), we can begin to draw relations between Winkler’s and Dobbin’s means of communicating through recorded images or remote sensing. Dobbin considers the emotive impact of their work strongly throughout their creative processes. They become active contributors, picking up content found through artifacts, or through storytelling or deep listening that speak to the vastly different experiences that people have had when living in, and traveling through the land or water. Each of their creative processes offer us perspective that turn a distributed media of existing stories into a conversation; through freezing time by creating thought provoking imagery, or through highlighting the emotive qualities of a place, or story.

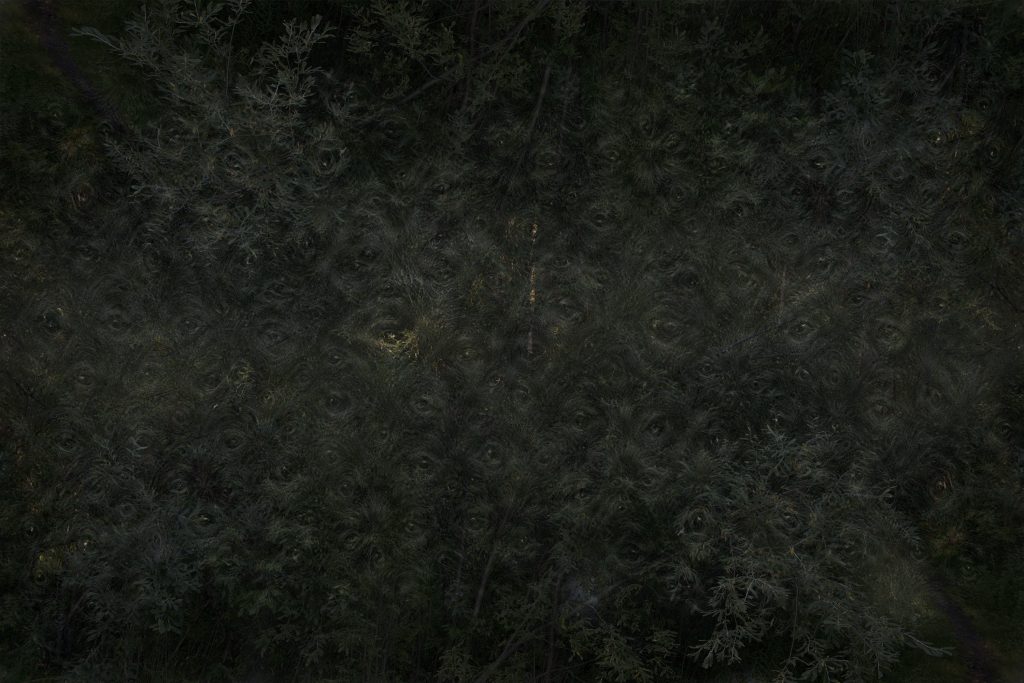

The Light of the Green Tunnel, Colour woodcut print, 20”x16”, Josh Winkler, 2018.

Michael McCormack

Curator for The Natural & The Manufactured, 2018.

Edited by Meg Walker

We would like to extend our gratitude to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation for their continuous stewardship of this land, and for welcoming this project, and to the staff and volunteers of the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre, Parks Canada, and CFYT 106.9 FM for their support.

INFO/FLOE is part of KIAC’s the Natural & the Manufactured residency and exhibition.

Further information:

KIAC N&M Program: www.naturalmanufactured.com

Josh Winkler: www.joshkwinkler.com

Lindsay Dobbin: www.lindsaydobbin.com

Michael McCormack: www.michaeldmccormack.com

References:

Barber, Bruce. Radio: Audio Arts Frightful Parent Dan Lander and Micah Lexier (eds.), Sound by Artists (Toronto and Banff: Art Metropole and Walter Phillips Gallery, 1990), pp. 109-137.

Bassett, Caroline. Remote Sensing in Caroline A. Jones (ed.), Sensorium: Embodied Experience. Technology and Contemporary Art (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2006) pp.200-201.

Peters, John Durham. Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2000.

Turck, Thomas J. and.Lehman Turck, Diane L. Trading Posts along the Yukon River: Noochuloghoyet Trading Post in Historical Context. Arctic, Vol. 45, No.1, March 1992, pp. 51-61.

Vipond, Mary. Listening In: The First Decade of Canadian Broadcasting, 1922 – 1932. McGill University Press, Montréal, 1992.

Winkler, Josh. The Chilkoot Trail Artist Residency. September 30, 2018. BLOG entry for WInkler’s website http://joshkwinkler.com/blog/2018/7/31/the-chilkoot-trail-artist-residenccy